In his seven-minute YouTube video, which has already received 12,000 views, Canadian snowshoe guide Dave Marrone makes the strongest case yet for traditional snowshoes. Marrone declares that traditional snowshoes are “lighter, more comfortable, and have better float”. He notes that they “don’t slip into the snow as much, the snow doesn’t stick to them as much, and they handle the slush.” But where is the future of traditional snowshoes headed?

Benefits of Traditional Snowshoes

To race well or to walk up a mountain, we must buy modern snowshoes. And other than making their bell-like sounds, our smaller aluminum shoes work fine on packed or groomed trails – as long as the temperature is 30 degrees below zero or higher.

However, longer traditional snowshoes are widely considered superior for walking long distances off-trail, where the snow is neither packed nor groomed. Because they are almost silent — and sound as natural as the forest — traditional snowshoes are also better when we are hunting or when we just want to walk very quietly through a natural winter landscape. And the decking on wooden snowshoes holds up at temperatures of 30 degrees below zero and lower, while plastic decking does not.

So perhaps all of us should be concerned that of the 200,000 pairs of new snowshoes that will be sold this year, fewer than 10,000 will be traditional snowshoes made out of wood and rawhide. With only a handful of companies still making them — almost all of them by Faber & Co., Country Ways, Iverson, GV Snowshoes, and Maine Guide Snowshoes — can traditional snowshoes survive?

Read More: Traditional Wooden Snowshoes: Shapes, Designs & Names

Future of Traditional Snowshoes

“Making traditional snowshoes is hard to do,” says Guy Faber, president of Faber & Co., a Quebec enterprise which has been making traditional snowshoes continuously since the late 1800s. “There are problems in production, ash wood is getting harder to get, and there is only one tannery left in Canada,” Faber told Snowshoe Magazine. “Wooden snowshoes could disappear.”

Dyke Williams, co-founder, and president of the Minneapolis company Country Ways is more optimistic. “We are determined to see it go ahead,” Williams told Snowshoe Magazine. Country Ways is the main company in the world selling snowshoe kits. Williams points out how easy it is to show people how to make their own traditional snowshoes.

The latest threat to traditional snowshoes is a bug. Around the year 2002, a beetle called the emerald ash borer arrived in North America from Asia. Since then across much of the United States and Canada tens of millions of ash trees have died.

“We do know how to laminate wood that is stronger and lighter than ash,” Williams says. “Ash is best, and it’s less fuss than laminate, but if the borer beetle becomes an issue, we have another option.”

Demand For Traditional Snowshoes

The remaining traditional snowshoe companies sell a lot of their snowshoes to people in Alaska and northern Canada. Some people buy traditional shoes as decorations for their walls.

Keeping The Numbers Up

Since 1987, Guy Faber and his brother Richard have been managing and leading the company founded in the late 1800s by their great-grandparents, Noe Sioui and Celide Gros-Louis. From their Quebec factory, Faber & Co. now produces 5,000 pairs of traditional snowshoes each year — and 45,000 modern pairs.

Quality Materials

The Iverson company of Michigan has been making traditional snowshoes since 1954. Throughout the 50 years since its founding by Clarence Iverson, Iverson has made snowshoes from white ash and rawhide. Today they produce 17 models and sell some of them as kits.

Iverson takes pride in the flotation, flexibility, and durability of their shoes. They remind us on their website of the benefits of quiet wooden snowshoes: “Break a trail in deep snow (and) take some pictures of the critters you haven’t spooked by the clanking of metal.”

Make Your Own Traditional SnowShoes

Dyke Williams and his business partner Greg Wilcox now run Country Ways. The company began in Williams’ garage in suburban Minneapolis in 1972. 80 percent of its sales are through being do-it-yourself snowshoe kits. Country Ways sells shoes and kits to educators, colleges, schools, nature centers, and scout clubs in 16 countries.

Williams was inspired to start the enterprise after six years as an Outward Bound instructor. “From our outdoor challenge program, we realized that kids enjoyed making shoes from their own kits.”

Even expedition outfitters buy Country Ways snowshoes and kits and Williams is finding that “demand remains surprisingly strong.” All of Country Ways’ shoes have frames made of straight-grain white ash. And Williams is proud that their nylon webbing is so strong and durable that “in 42 years, we know of no failure of our lacing material.”

Read More: Make Your Own Traditional Snowshoes From Scratch

Importance Of The Tradition

As the 21st Century snowshoe community, we may give up a great deal if we abandon traditional snowshoes. For starters, we may give up comfort, flotation, and the ability to walk smoothly through both snow and slush when we go off-trail for long distances. We may give up the ability to snowshoe when the temperature dips under 30 degrees below zero. And we may give up the ability to hunt quietly on snowshoes or to walk through natural winter habitats in near-silence.

But something even more fundamental is at stake: our connection with a continuous 6,000-year tradition.

Our tradition began some 6,000 years ago when the first Central Asian tribesmen used hide straps to lash a slate of wood to the bottom of each foot. They then walked across the snow on these “shoeskis” without sinking.

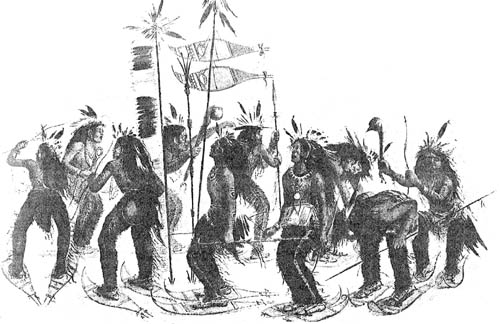

Our tradition continued as the men and women of almost every Native American tribe in North America developed an oblong-oval webbed snowshoe.

Alaskan Tribes

The Athabascan, the Inuit, and other Alaskan tribes wore long snowshoes. They had a hard time making turns in their shoes. However, they moved fast enough to keep up with dogs with a sled across Alaska’s vast open spaces.

Woodland Tribes

The Ojibwe (also called the Ojibwa or Chippewa) walked across the snow with shoes fashioned with a pointed tip and an upturned toe. Woodland tribes like the Ojibwe and the Iroquois needed both ends of the shoe to be pointed. That way they had the speed and agility to follow buffalo and other game across challenging and varied terrain, from prairie meadows to thick forests. The Cree wore a six-foot shoe and others wore shoes as long as seven feet.

The Huron – the Maine, the Michigan, and the Algonquin – moved gracefully through open places on their wider snowshoes. Today these shoes remind us of big tennis rackets.

Plains Tribes

And many Indians, including many of the Plains Indians, found it much easier to hunt buffalo in their Bear Paw snowshoes – short and wide with a round tail. These shoes were strong and lightweight and gave them optimum flotation. Bear Paws enabled them to handle a heavy load as they moved easily through versatile terrain. From the Bear Paw, primarily, emerged our modern snowshoes.

All along the way across thousands of years, the Native Americans of what became Canada and the United States have steamed and bent wood into frames with shapes of remarkable sophistication. They learned that wood does not fill with water and freeze. Also, ash wood is so strong and pliable that it makes the best snowshoes. And they learned that the rawhide from caribou, moose, elk, or deer makes the best decking and strips for snowshoe lacings.

Keeping The Tradition Alive

So there is a great deal at stake when we choose our snowshoes. And there is a great deal at stake in whether enterprises like Faber & Co. and Country Ways can continue to profitably produce traditional snowshoes.

Along with comfortable and quiet walking off well-worn trails – for as long as we choose to walk – it is our 6,000-year tradition that is at stake. We walk in the time-honored habits of Native hunter-gatherers – and the time-tested skills of Native craftsmen and artisans – each time that we take a walk in traditional snowshoes.

GV Snowshoes’ traditional models

Faber & Co. traditional snowshoes

To view Dave Marrone’s YouTube video:

And now Faber no longer makes traditional snowshoes. The worlds largest and best maker no longer makes them. I am at a loss for words. I get the supply and demand, but seriously. What’s next, Quebec also stopping production of maple syrup; centuries ago the snowshoe is what helped make syrup production even possible. I’m glad I learned how make my own. Traditions continue to die…

Where to get webbing lacing?

Too bad the audio is so low….